Brain and Spine Conditions

The pressure inside your skull is called intracranial pressure (ICP). ICP is determined by the size of your brain, the amount of blood in your head, and the amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) in your head. When ICP is outside of the normal range, different symptoms can appear and affects patient’s lives or may lead to other conditions.

- For Patients

- For Physicians

Intracranial Hypertension and Hypotension

The pressure inside your skull is called intracranial pressure (ICP). It depends on three things:1

- The size of your brain

- The amount of blood in your head

- How much cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is inside your head

CSF is a clear liquid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord. It cushions and protects them, carries nutrients and hormones, and helps filter out waste.2

Intracranial hypertension (ICH) happens when the pressure inside your skull is too high.1 This can happen because of:

- Brain injuries, swelling, or tumors

- Blood clots in the brain

- Increased pressure in your neck, chest, or belly

Sometimes, doctors don’t know the cause of ICH. When that happens, it’s called idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH).

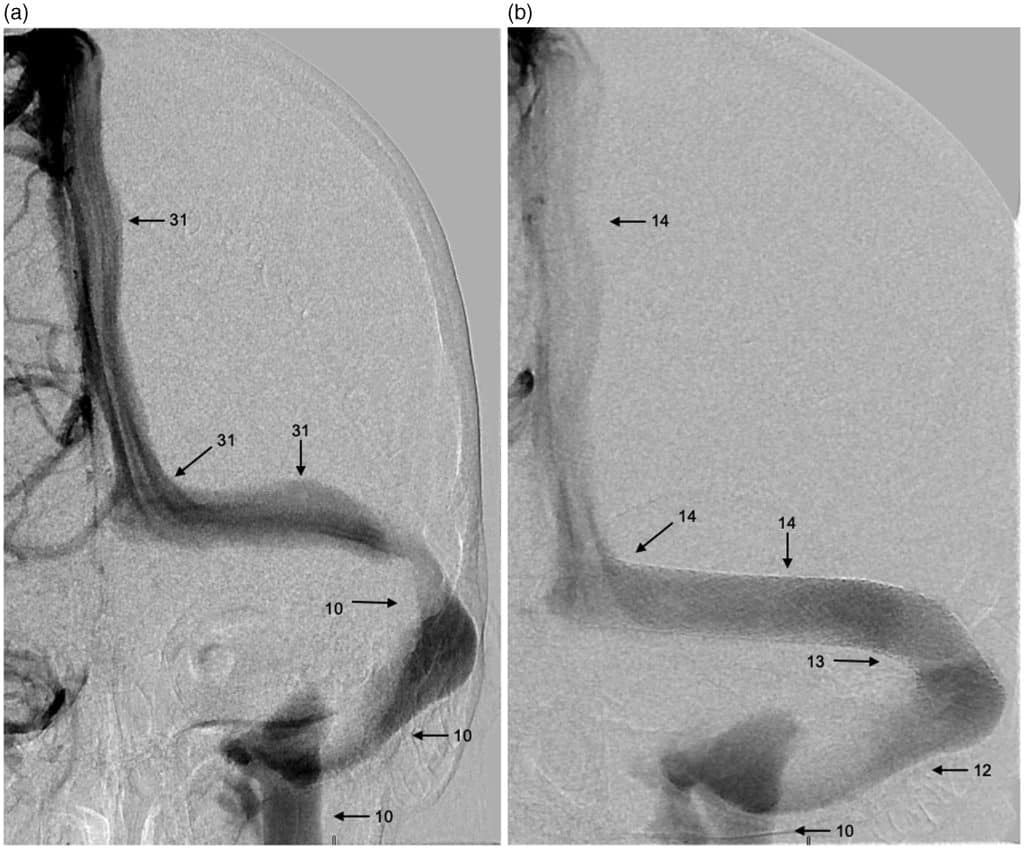

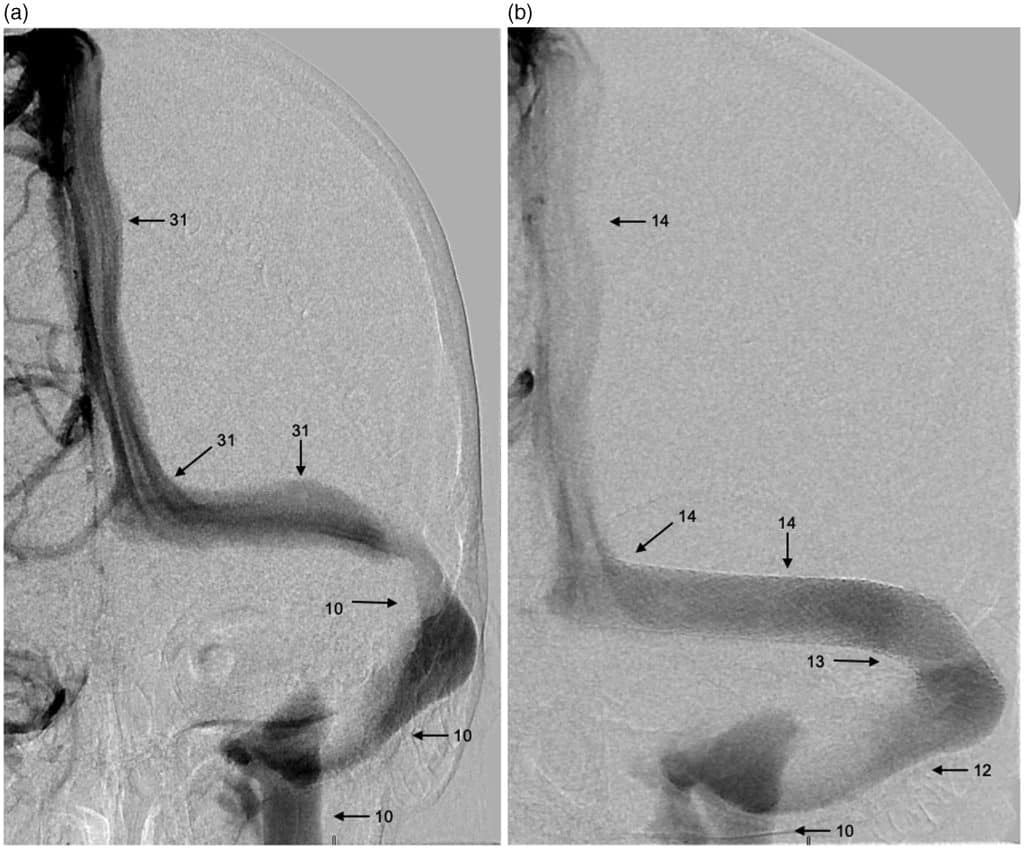

Recently, doctors have found that ICH can also happen when veins that drain blood from the brain get squeezed or compressed—especially when this happens to the venous sinuses and internal jugular veins (IJV).3

Symptoms4

Common symptoms of ICH include:

- Severe headaches

- Papilledema (swelling of the nerves of the eye), which can cause:

- Temporary vision loss

- Blurry vision

- Double vision

- Pulsatile tinnitus (a whooshing sound in your ears that matches your heartbeat)

- Dizziness

- Brain fog

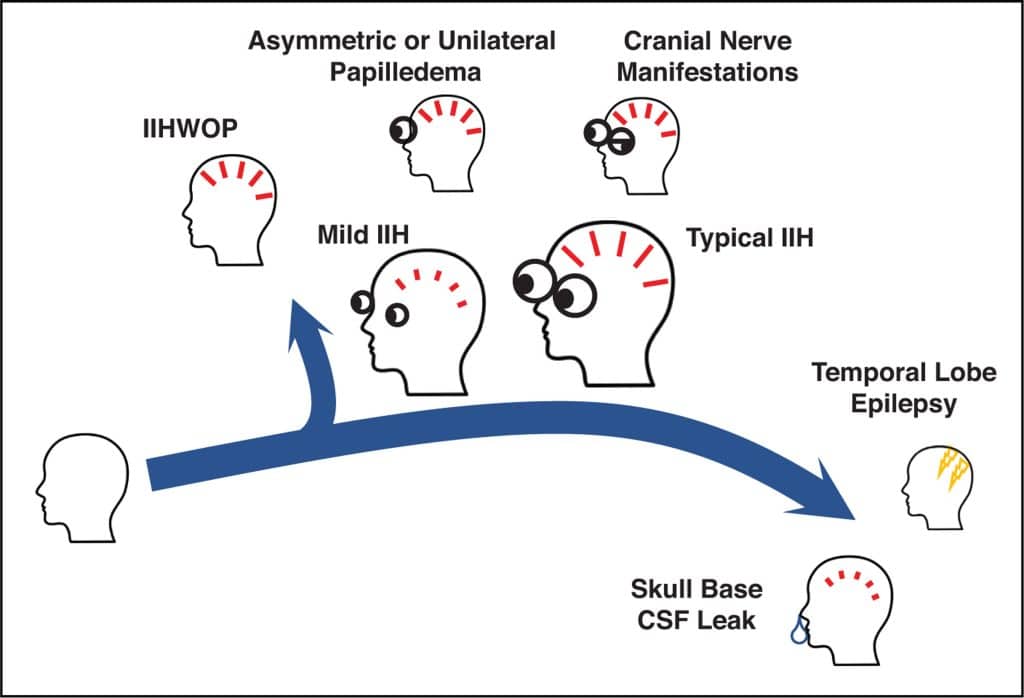

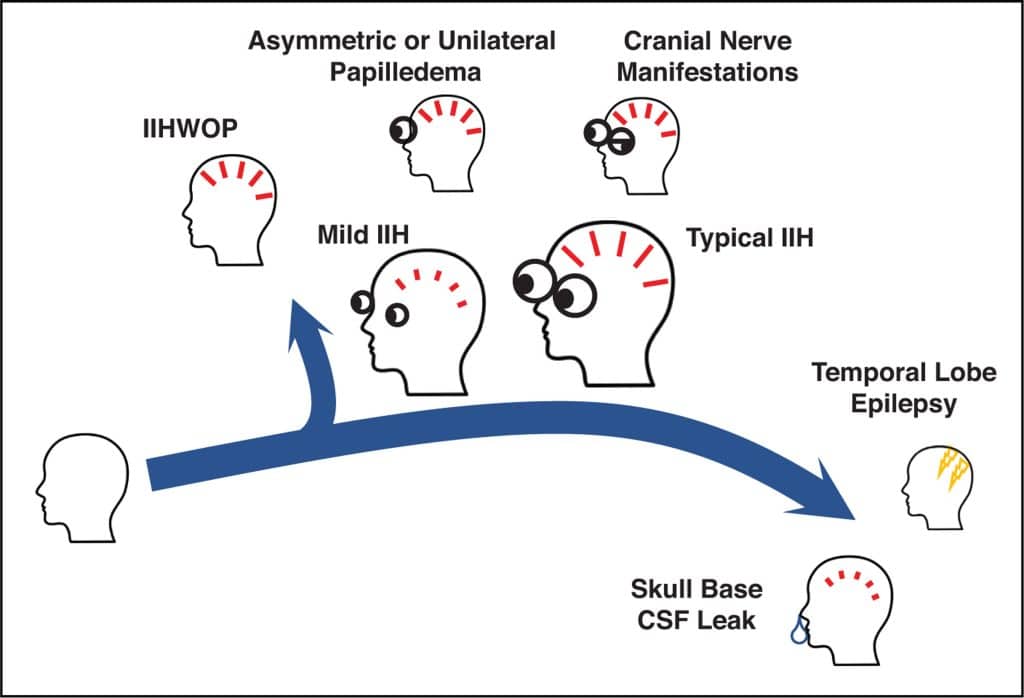

Recently, doctors have noticed there may be other symptoms associated with ICH. Newer symptoms doctors have noticed include:

- CSF rhinorrhea (CSF leaking from the brain through the nose)

- People with CSF leaks may have low pressure (intracranial hypotension) instead of high pressure and may not have the usual ICH symptoms—but are more likely to have a compressed blood vessel.5

- Meningitis (swelling and infection around the brain)

- Facial weakness

- Trouble controlling eye movements

- Temporal lobe epilepsy (a type of seizure)

Impact

ICH is more common in people with a higher body mass index (BMI) and/or a lower income. ICH cases are rising fast. In 2017, there were 6 times more people with IIH than in 2003. People with ICH go to the hospital 5 times more often than people without it.6

Treatment7

Treatment depends on the person’s symptoms and what is causing the high or low pressure. Options include:

- Losing weight

- Taking diuretics (medicines that help remove extra water from the body)

- Putting a stent (small metal tube) into a compressed vein to lower pressure

- This can be in a vein inside the skull or a larger vein in the neck called the internal jugular vein (IJV)

- Putting in a shunt (a device that drains CSF to another part of the body)

- Surgery to make more space around the jugular vein by removing bone

- Lumbar puncture (removing extra CSF with a needle in the lower back)

SAFIRE

There is an urgent need for more awareness, better treatments, and insurance coverage for ICH. SAFIRE is raising money to fund research for new, less invasive treatments. SAFIRE will aim to help patients find the right care team for their needs by generating a network of physicians who are experts in their fields.

References

- Wilson MH. Monro-Kellie 2.0: The dynamic vascular and venous pathophysiological components of intracranial pressure. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(8):1338–1350.

- Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S, Johanson CE. A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp Neurol. 2015;273:57–68.

- Fargen KM, Midtlien JP, Margraf CR, Hui FK. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension pathogenesis: The jugular hypothesis. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024:15910199241270660.

- Chen BS, Britton JOT. Expanding the clinical spectrum of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2023;36(1):43–50.

- Manupipatpong S, Primiani CT, Fargen KM, et al. Jugular venous narrowing and spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks: A case-control study exploring association and proposed mechanism. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024;30(6):812–818.

- Miah L, Strafford H, Fonferko-Shadrach B, et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Health Care Outcomes in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Neurology. 2021;96(8):e1251–e1261.

- Fargen KM, Coffman S, Torosian T, Brinjikji W, Nye BL, Hui F. “Idiopathic” intracranial hypertension: An update from neurointerventional research for clinicians. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(4):03331024231161323.

Overview

The following three factors determine intracranial pressure (ICP)1:

- The mass of the brain parenchyma

- The amount of cerebral blood

- The amount of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) within the skull

CSF, a clear fluid produced primarily by the choroid plexus, provides mechanical cushioning, facilitates the delivery of nutrients and hormones, and clears metabolic waste.2

Intracranial Hypertension (ICH)

ICH occurs when ICP exceeds the compensatory capacity of the intracranial compartment.1 This may occur in the following situations:

- Traumatic brain injury (TBI)

- Cerebral edema

- Space-occupying lesions (e.g., tumors)

- Cerebral venous thrombosis

- Increased intrathoracic, intrabdominal, or central venous pressure

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) occurs when no structural, vascular, or infectious etiology is identified as the cause of the ICH. Emerging evidence implicates extracranial venous outflow obstruction—particularly stenosis or compression of the dural venous sinuses and internal jugular veins (IJVs)—as an underrecognized contributor to elevated ICP.3

Clinical Presentation4

Common symptoms of ICH include:

- Severe headache

- Papilledema with transient visual obscurations, blurred vision, or diplopia

- Pulsatile tinnitus

- Dizziness

- Brain fog

Recently, the following symptoms have been shown to be associated with ICH:

- CSF rhinorrhea

-

- Patients with CSF leaks may be less likely to experience the “classic” symptoms of ICH, as they may have intracranial hypotension (low pressure) but are much more likely to have a compressed blood vessel.5

- Meningitis

- Lower cranial neuropathies or facial nerve paresis

- Ocular motor nerve palsies

- Temporal lobe epilepsy

Intracranial Hypotension

Low ICP may result from spontaneous or iatrogenic CSF leaks, overdrainage of CSF shunts, or post–lumbar puncture effects. Clinical features differ from ICH but can coexist with venous outflow obstruction.

Epidemiology & Health Impact

The incidence of IIH has risen sharply; between 2003 and 2017, prevalence increased sixfold. It has been shown that IIH is more prevalent among individuals with elevated BMI and lower socioeconomic status. Patients with ICH have ~5 times the rate of unplanned hospital admissions compared to controls.6

Management7

Therapeutic strategies are tailored to etiology and symptom burden. Potential treatment options include:

- Lifestyle modification (notably weight reduction)

- Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors and other diuretics

- Endovascular stenting of stenotic venous sinuses or IJVs

- CSF diversion via ventriculoperitoneal or lumboperitoneal shunt

- Surgical decompression to relieve jugular vein entrapment (e.g., styloidectomy, C1 transverse process resection)

- Serial or therapeutic lumbar puncture in select cases

SAFIRE Initiative

There remains an unmet need for heightened clinical recognition, standardized diagnostic pathways, and evidence-based, individualized treatment options for ICP disorders. SAFIRE is helping to raise funds for research on minimally invasive therapeutic modalities and is aiming to connect patients with multidisciplinary care teams experienced in managing complex ICP pathologies.

References

- Wilson MH. Monro-Kellie 2.0: The dynamic vascular and venous pathophysiological components of intracranial pressure. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2016;36(8):1338–1350.

- Spector R, Robert Snodgrass S, Johanson CE. A balanced view of the cerebrospinal fluid composition and functions: Focus on adult humans. Exp Neurol. 2015;273:57–68.

- Fargen KM, Midtlien JP, Margraf CR, Hui FK. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension pathogenesis: The jugular hypothesis. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024:15910199241270660.

- Chen BS, Britton JOT. Expanding the clinical spectrum of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Current Opinion in Neurology. 2023;36(1):43–50.

- Manupipatpong S, Primiani CT, Fargen KM, et al. Jugular venous narrowing and spontaneous spinal cerebrospinal fluid leaks: A case-control study exploring association and proposed mechanism. Interv Neuroradiol. 2024;30(6):812–818.

- Miah L, Strafford H, Fonferko-Shadrach B, et al. Incidence, Prevalence, and Health Care Outcomes in Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension. Neurology. 2021;96(8):e1251–e1261.

- Fargen KM, Coffman S, Torosian T, Brinjikji W, Nye BL, Hui F. “Idiopathic” intracranial hypertension: An update from neurointerventional research for clinicians. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(4):03331024231161323.